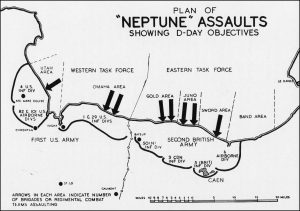

On 15th May General Bernard Law Montgomery, the British commander of the Allied land forces told the assembled allied commanders that the allied troops would press on inland south of Caen, securing airfields and providing a shield for a American breakout towards Brittany. But that did not happen. Instead, after brief battles on D Day and D+1 there was no further attempt to take the city until July. To some American and British air force, commanders it seemed that the British were not trying hard enough and that Montgomery was making excuses for failure.

General Bernard Law Montgomery is a controversial figure. A good Dunkirk and an outstanding record training soldiers troops took him to Army command in North Africa at El Alemein. He was the talisman of success for the British, inspiring soldiers to believe in victory. Monty was also arrogant, abrasive and undiplomatic, and far from universally popular even within the British Army. A Time Magazine article dated 10 January 1944, says that British staff officers circulated the description “Indomitable in defeat, indefatigable in attack, insufferable in victory!” attributed to Churchill.

The delay in capturing Caen strained relationships between soldiers and airmen and between Montgomery and his boss Eisenhower. Some members of Eisenhower’s staff even tried to get Montgomery dismissed. Americans started to think that they were bearing an unfair share of the fight and casualties. Its an idea that has persisted: the only mention Stephen Spielberg included about the British in Saving Private Ryan was that the British were “drinking tea in front of Caen”. But is that fair? To what extent was Montgomery to blame? Is there anywhere on the modern day battlefields of Normandy that can provide an insight.

Failings in the 3rd British Division

The task of the assaulting divisions is to break through the coastal defences and advance some ten miles inland on D Day. Great speed and boldness will be required to achieve this. …As soon as the beach defences have been penetrated not a moment must be lost.

1st British Corps Operation order No 1 5 May 1944

There were questions about the performance of the 3rd British Infantry Division tasked with capturing Caen. This Division landed on a single brigade front on Sword Beach. At H+295 (12.30pm) the 185th infantry Brigade Group scheduled to have landed and assembled its infantry tanks and artillery to d dash for Caen. But this did not happen.

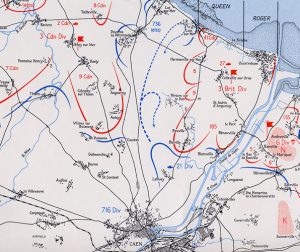

The brigade landed roughly on schedule, with the infantry ashore around 10.00 but congestion on the beaches meant that none of the armour or supporting vehicles were off the beach by 12.30, when Brigade commander started the advance with infantry only on foot, partially by a circuitous route. The assault brigade had also met unexpected resistance at a German position south of Coleville-sur-Mer which imposed a further delay. By late afternoon the leading infantry battalion had reached the edge of Lebisey wood, on the ridge just north of Caen. Around the same time the German 21st Panzer Division launched the only German armoured attack in D Day. By the time this was stopped there would be no further advance towards Caen on D Day.

The next day, D+1, 7th June, 185th Brigade mounted an attack with a single battalion. This turned into a disaster as unsupported infantry tangled with German tanks. The Brigade commander K P (Kipper) Smith was dismissed.

Post war there has been much criticism of the Sword beach plan. Why land on a single brigade front? In rehearsals there were questions the performance of the brigade commander. Why was he given a critical role in the assault?

Staff college studies have also pointed to the 3rd Division becoming overloaded with tasks. Besides capturing Caen they were to protect their own beachhead, link up with the Canadians to their west and provide artillery and armour to support the airborne troops to their east.

Retired British General Mike Reynolds book “Eagles and Bulldogs” (2003) compares the fortunes of 3rd British and 29th US Divisions in Normandy. His chief criticism are of the divisional and brigade commanders, whose performance was found wanting,. and the failure of the British Army to train its infantry divisional and brigade commanders combine armour and infantry effectively.

Some historians such as Max Hastings have argued that man for man and unit for unit the Germans were better than the British, and Americans, who could only advance through brute force. However, historians such as John Buckley and Terry Copp have challenged this interpretation.

As God once said, and I think rightly.

Bernard Law Montgomery

Poor Allied Intelligence and Unrealistic expectations

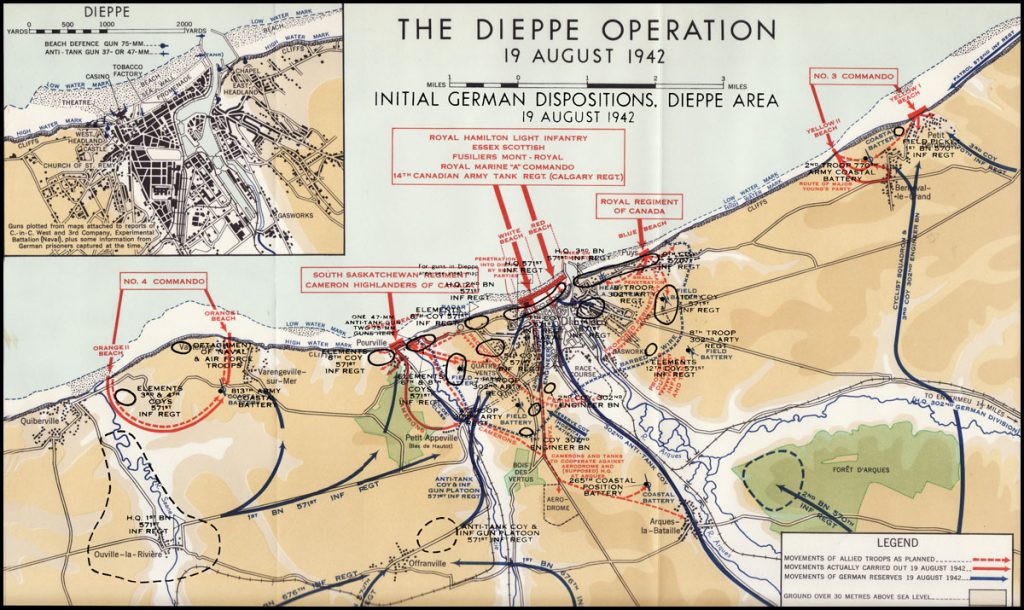

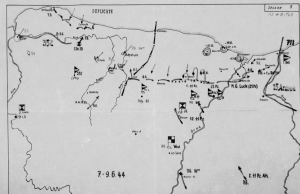

infantry, anti tank guns and artillery of the 21st Panzer Division inland from Sword Beach. The red crosses show the targets for the Allied fire plan

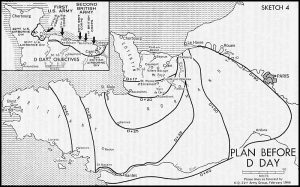

One of the myths of D day is that the allies had supremely good intelligence. The Code breakers read the Germans communications. The Invasions maps showed every detail of the German defences, prepared from aerial photographs and with the aid of the gallant French Resistance. All true, – up to a point. There were a few things wrong with the Allied Intelligence brief. During the early months of 1944 the Germans moved several formations much closer to the coast as part of Rommel’s plan to defeat the allies on the beaches. Allied intelligence missed the presence of soldiers from the 352nd Infantry Division doubling the number of defenders at Omaha Beach. They also missed reinforcements to the 716th Division sector North of Caen, including half of the infantry and the anti tank battalion of the 21st Panzer Division. (The 21st Panzer Division was an incredible organisation commanded by an extraordinary figure – General Edgar Feuchtinger.) By 15th May, the day of Montgomery’s briefing, there could not be a dash inland to seize Caen. The Germans were already there in force.

When Caen was set as an objective, back in mid 1943 the planners based their assumptions on Germans forces in France consisting of between a best case of 20 divisions and a worst case of 50 divisions. By 6th June the Germans had 60 divisions in France, and chosen to deploy them as close to the coast as possible. It may be that a ten mile advance ashore after an assault landing was not achievable objective

The Germans did a good job of defending Caen.

War is a kind of democracy: The enemy gets a say. The biggest single reason why the British and Canadians advance was so slow was because the Germans committed the necessary resources to stop them. German doctrine required the commander to determine a point of main effort. In summer 1944 in Normandy the Germans decided that they would put their main effort against Caen. On D Day itself the German local Commander General Marcks organised the armoured counter attack from Caen. In the following days two more Panzer Divisions were brought up between Caen and Bayeux. The Germans would continue to reinforce the Caen sector through out June, bringing a whole SS Panzer Corps and about 100 heavy Tiger tanks to face the British and Canadians.

To be fair to the Allied commanders and their staff, they had studied German doctrine and predicted that the Germans would strike at the British and Canadian forces. This knowledge drove the allied strategy for the British and Canadians to act a s a shield was the basis for the role outlines as the British and e Germans who needed to throw the allies into the sea.

Eisenhower should take some of the Blame.

By and large Eisenhower is praised by everybody for taking the decision to launch D Day in marginal weather, while Montgomery takes the blame for failing to achieve the objectives. This isn’t wholly fair. Launching D Day in poor weather had consequences.

- High sea states caused many problems. Some landing craft had to turn back to England and others were swamped. Few of the Amphibious DD Tanks swam ashore. Difficulties operating Rhino ferries slowed the landings.

- The aerial bombardment was curtailed reducing the fire suipport on the beaches.

- There were problems clearing obstacles and getting vehicles off the beach

This is an argument put forward by Stephen Badsey in “Culture Controversy, Cherbourg and Caen” a chapter in “The Normandy Campaign 1944 Sixty Years on”

Was Montgomery Over Cautious?

“The commander must decide how he will fight the battle before it begins. He must then decide who he will use the military effort at his disposal to force the battle to swing the way he wishes it to go; he must make the enemy dance to his tune from the beginning and not vice versa.”

Bernard Law Montgomery

One of the major criticisms of Montgomery is that he was overcautious and relied on overwhelming firepower. Behind this criticism is the suggestion that the British were not pulling their weight and that America was bearing a disproportionate proportion of the effort and cost of the Normandy Campaign, It is true that the USA suffered higher losses than the British and Canadians 125,847 compared to 83,825, but more American were landed. Expressed as a proportion the casualty rates for both allied forces was just over 10% of the troops landed by the end of August.

(10.29% of US and 10.1% for the British)

Montgomery’s style was a series of methodical attacks supported by as much fire power as possible following as closely as possible his script for the battle. This was key to winning the confidence and loyalty of his men. For the first half of the war the British had tried to do too much with too little in too much of a hurry. There was also the shadow of the Somme. The men who served in Normandy grew up with the tales their fathers told of ill prepared attacks and huge losses. My father, a Normandy veteran, told me that if Montgomery was in charge, everything possible had been done to make sure that the operation would be successful.

The methodical approach suited the British Liberation Army. The experience of the 3rd British Division on D Day suggests that it wasn’t very good at improvised combined arms operations. This was a failing that would be shown up during the campaign.

There was a further reason for British caution. In 1944, after nearly five years of war, the British had few men to spare to replace casualties. Casualty rates in Normandy were much higher than the allies expected. The US Army could draw on infantry replacements from formations still in the USA. The British would have to reduce thew size of their army.

What Can we Blame Montgomery for?

Montgomery probably didn’t give much thought to the 15 May phase lines that would cause so much trouble. According to Lieutenant Colonel Kit Dawney, Montgomery’s Military Assistant, who drew them, the intermediate lines were spaced equally. According to Dawney, Montgomery did not care groundwise where he would be between D+1 and D+90 as he was confident we would beat the Germans in three months. He was not going to capture ground. He was going to destroy the enemy. (From Hamilton Montgomery Master of the Battlefield)

Arguably Montgomery had a point. As long as the Germans could not throw the allies into the sea, and the Allied forces ashore continued to expand the Allies would achieve the aim of Operation Overlord. The conduct of the battle rest was to wear down the Germans as efficiently as possible, even if it occasionally meant giving up ground.

Soldiers needed to be given clear geographic objectives even if the aim was to provoke an attritional battle – what Montgomery described as the “dogfight.” Military history is full of examples of troops being ordered to do “Capture X” with the commander fairly certain that the enemy won’t let them.

Those that have followed the accounts of British operations so far will have realised that General Montgomery’s named intentions were clearly stated, that in no case were their geographical objective reached; yet when each operation concluded with its stated object unrealised, he asserted he was satisfied with the result. To observers… the satisfaction he professed was incomprehensible.

Ellis Victory in The West Volume 1: The Battle for Normandy p355

The report lines came to be the focus of criticism. While he could structure his plans around destroying the enemy. the media and public associated success with conquering ground. Montgomery’s blindness to this did not help Eisenhower manage expectations at a time when there was pressure for progress and a growing fear that operations had bogged down.

Among the traits that irritated and infuriated Montgomery’s claims of infallibility particularly grated – and was easily disproved by critics. Eisenhower remarked that plans always change, and good commanders adapt. But Montgomery would claim that battle had played out as he had always predicted. To see examples, read “Decision in Normandy”. Carlo D’Este documented the backtracking by Montgomery.

Why did the British put up with Montgomery?

Montgomery was probably the most influential British field commander of the Second World War. He stood out in 1940 as the only divisional commander to use the phoney war of 1939-40 to train his division for mobile war. After Dunkirk his training methods influenced the whole of the Home Army, and still shape the modern British Army. In 1942 in North Africa he restored the morale of British army and confidence in their ability to beat the Germans. That wasn’t trivial. By 1942 British soldiers had begun to lose confidence in their commanders after a long run of disasters. A contemporary joke was that the initials BEF, (British Expeditionary Force) really stood for Back Every Friday – which is why the British in 1944 were the British Liberation Army. Montgomery’s methods are analysed in Stephen Hart’s “Colossal Cracks” (2007) which is a text book at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Where to see this story in Normandy?

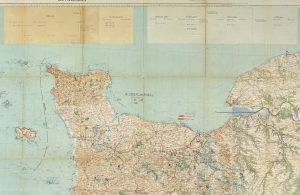

Sword beach is not as heavily visited as Omaha beach. There is no Interpretation centre or commemorative preserved battlefield. There is evidence of the battle, but dotted around the resort villages that stretch from Ouestrhem to Lion-sur-Mer. Some of the concrete emplacements remain along the coast and inland, but most were removed.

The village of Colleville-sur-Mer changed its name to Colleville-Montgomery in honour of the British commander. There is a fine statue of him in on the road from the beach to the village. For many years this is where the British Normandy Veterans Association held their annual parade.

The Hillman fortified position that caused so many problems has been preserved by local volunteers and dedicated to the Suffolk Regiment.

There is nothing to interpret or commemorate the defeat of the German armoured counter attack on D Day. But the landscape south of Periers Ridge is still open countryside. The city of Caen has expanded north and villages such as Lebesiy and Epron are now suburbs. Enough of Lebisy wood is left for a battlefield visitor to see where the Germans halted 3rd ambushed 185 Brigade on D+!.

There is an exhibition on the post D Day battles for Caen at the museum at Bayeux just down from the Commonwealth Bayeux War Cemetery. The main memorials of the inland battles are the war cemeteries, each a reminder. The Canadians have done more than the British to explain their role with a series of interpretation boards. There are a few unit memorials to mark particularly grim battles.